Expert insights

Surrounding all mothers with the maternal and postpartum care they deserve

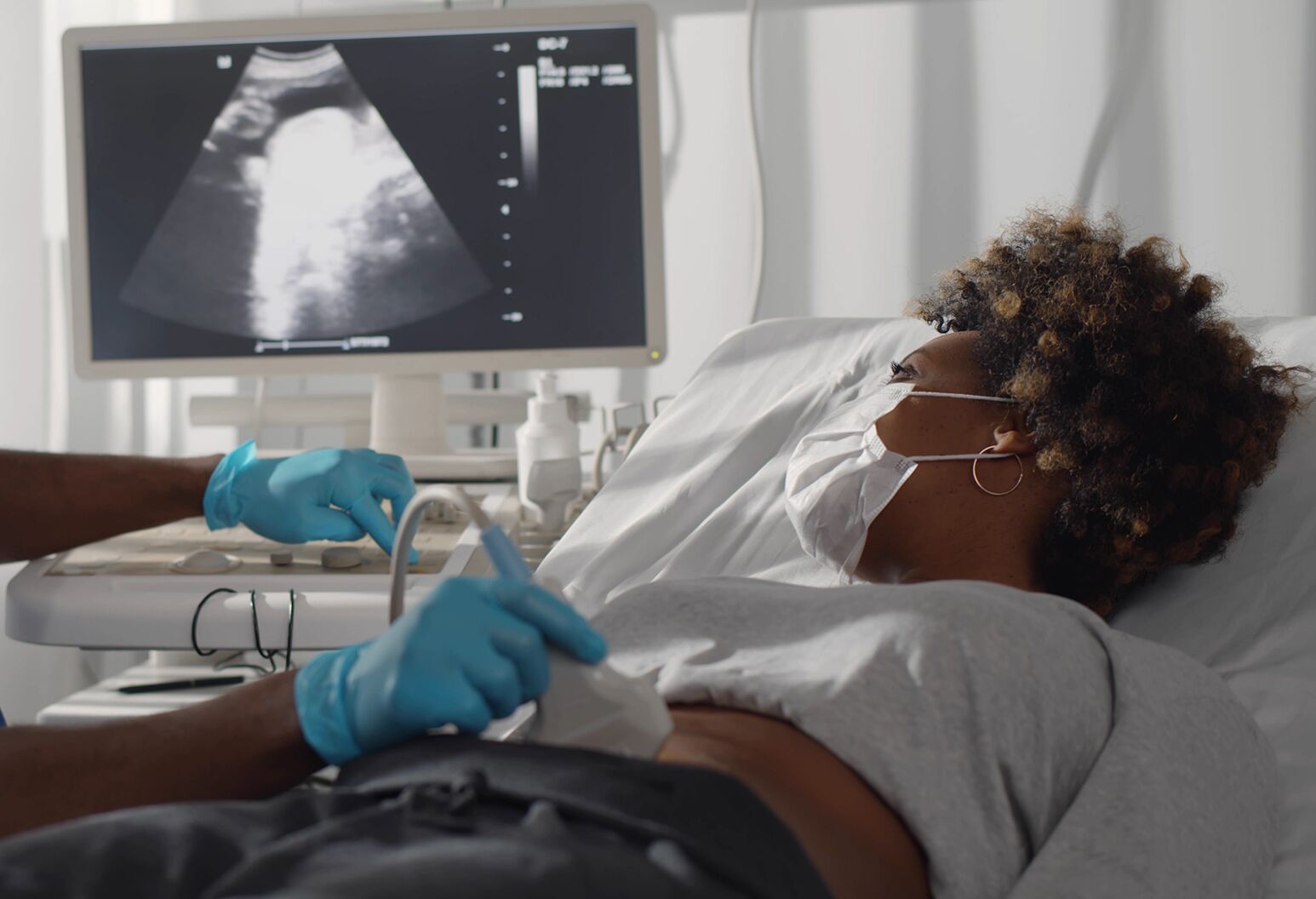

Maternal health care shouldn’t end when labor stops. Here’s how we can improve maternal death outcomes.

Birth is not a single moment with a distinct beginning and end. Instead, pregnancy, delivery and parenthood are all part of a family’s ongoing health and wellness life cycle. So why don’t we treat it that way? Why, once a baby is delivered, do we shift all the focus on the baby and provide disjointed, often inequitable care to the mother and her family supporters?

The United States has the worst maternal health care outcomes among industrialized nations—700 birthing people die every year from pregnancy- and delivery-related complications—a number that continues trending upward. Worse, 84% of maternal deaths are preventable and occur disproportionately in our underrepresented minority communities. Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native women are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women, which is an abysmal illustration of the failings of our health care system.

Race alone is not a risk factor for maternal morbidity and mortality, but racism is. Data collected and analyzed for decades have repeatedly shown that structural, institutional racism and implicit bias contribute significantly to the disproportionately high maternal morbidity and mortality rates among Black women. This is not about hearts and minds—it’s about systems. Our maternal health care and delivery system is perfectly designed to give us these distressing outcomes. If we want to protect mothers and reduce morbidity and mortality, we need to fight our current system with a new one. We cannot rely on individual behavior, not on the part of the clinician or the part of the mother.

Northwell, in partnership with the Katz Institute for Women’s Health, launched the Center for Maternal Health, a program for new mothers at high risk of poor outcomes. The Center is committed to improving health by combating the institutional norms that contribute to structural racism and bias. One example of this approach is breaking down the barriers to getting connected to needed services. In this arena, we see that there are referral biases where only certain families are offered services, while others go without. By using health informatics and risk modeling to identify mothers for participation, we can eliminate this structural bias and make sure that anyone who qualifies has access to the most comprehensive services.

This concierge programming includes standardized assessments of mental health, cardiovascular specialty services and assistance with myriad social determinants of health. We also collaborate with moms on a wellness plan that considers all aspects of their health in a longitudinal way. We provided these services to all mothers, for free, regardless of their demographic or socioeconomic background. Our efforts have led to a 40% reduction in morbidity, including heart attack and stroke, among more than 3,500 women who went through the program. Those improvements were even greater for the Black women in the group.

The bottom line: We need to ensure that every single woman gets exactly what she needs every single time. There are a few key initiatives we can focus on to ensure quality treatment:

- Mandate 100% coverage of blood pressure cuffs and behavioral health care. We know two of the leading causes of death postpartum are behavioral health issues, including suicide and substance use disorders, and, especially for Black women, cardiac and coronary conditions. All mothers should have standardized and routinized behavioral health assessments and subsequent access to mental and behavioral health care before and after delivery. Further, we can train new mothers to regularly check their blood pressure and provide them with standardized instructions on what to do when they get troubling readings, but only if the appropriate equipment is covered by their insurance.

- Expand and incentivize non-medical pregnancy care. Pregnancy and delivery can be complex, but they do not always require the most complex medical interventions including cesarean surgery. We must expand access to midwives, doulas and alternative birthing centers, which promote non-interventional approaches.

- Create and execute universal assessments and care protocols. We need a standardized rubric for all postpartum mothers that alerts us to critical postpartum risk factors. Our patients’ answers can help us identify and address gaps in care. Standardization will help us eliminate bias as a risk factor.

- Standardize training for all health care personnel on bias in health care with a specific emphasis on birth justice. In order to be able to benefit as a health care system from information that women and their families are sharing with us, we must have the right tools to be able to hear and communicate without prejudice.

The good news is, reducing racial disparities in maternal health outcomes and saving new mothers’ lives is possible, and it does not necessarily require complex solutions. We have a lot of evidence-based strategies and tactics that work. We need to create new systems that use those strategies to provide the positive health outcomes we want to see.

Learn more about making your health a priority. Our women’s health navigators are here to answer your questions and can help you schedule an appointment.