Insights

Improved scoliosis surgery: Better results, less opioid exposure

An innovative pain management technique is reducing surgical pain and minimizing the risk of opioid dependency in kids who need scoliosis surgery

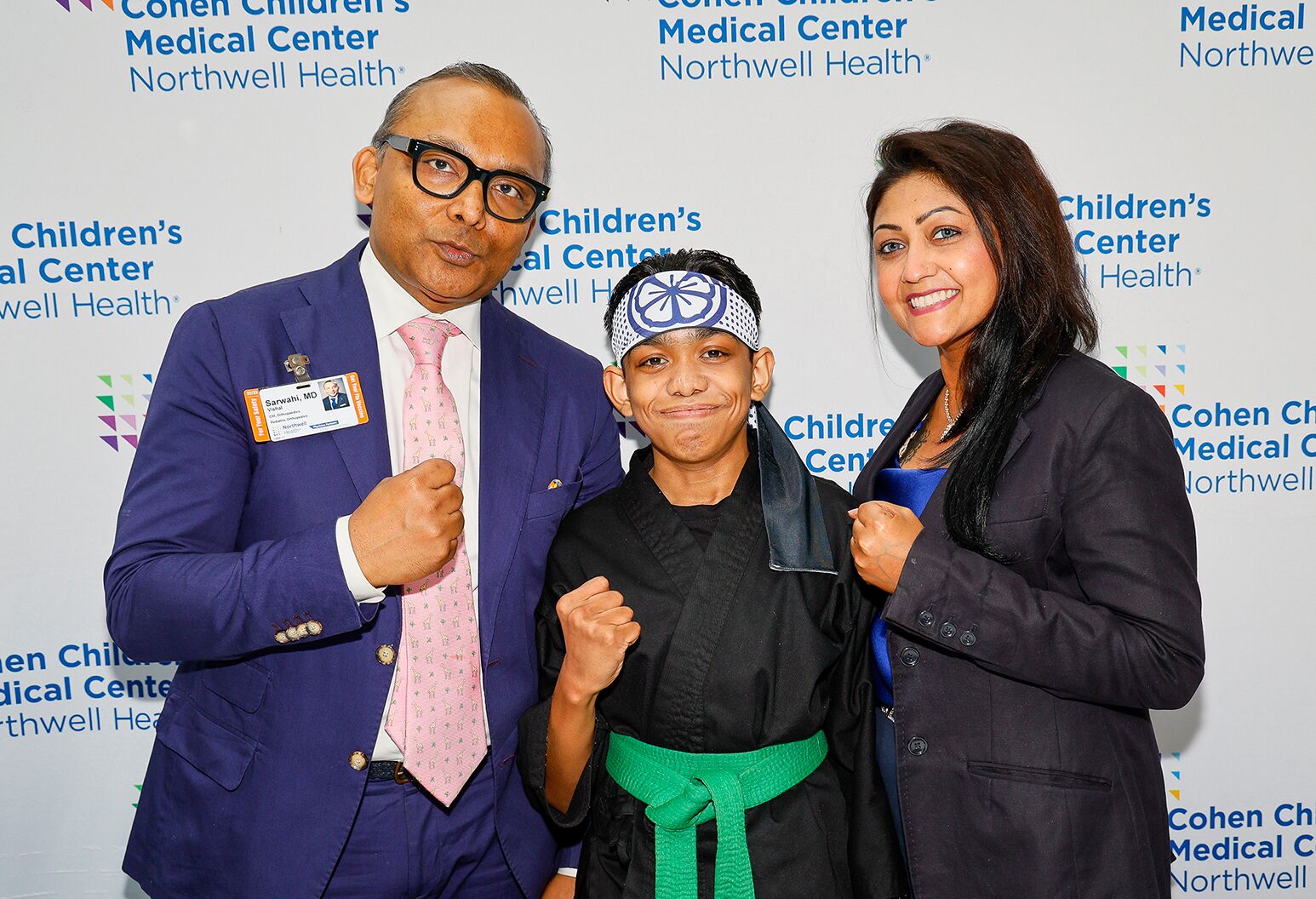

In 2018, spine surgeon Vishal Sarwahi, MD, met with two teenage patients who needed scoliosis surgery. The parents of the teens were deeply concerned — and not just about the surgery. Both teens had a history of opioid misuse, and, recalls Dr. Sarwahi, “This was around the time that the opioid epidemic was becoming a major problem.”

The concern was justified; for high schoolers, five days of exposure to opioid painkillers can raise the risk of future addiction issues by 33%, according to research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And that’s for children with no prior history of abuse.

A decade earlier, Dr. Sarwahi had developed minimally invasive techniques that dramatically reduce post-operative pain and recovery times. Now he had a new challenge. Could he create a protocol that would minimize or even eliminate opioid exposure for these vulnerable patients? The answer hinged upon an alternative method of delivering opioids that allowed for the best results at lower doses – Duramorph.

Pediatric scoliosis: a curve that disables

Up to nine million Americans are affected by scoliosis, a condition in which the spine develops a sideways curvature and an abnormal twist. It usually starts to become evident as children hit a growth spurt around the ages of 10 to 15 years.

“As patients age, these larger curves can continue to increase in size. They can become big enough that the deformed spine pushes on the lungs, affecting breathing,” Dr. Sarwahi says. “In severe cases, it can also affect the functioning of your heart. “To prevent that kind of progression, surgery is the best answer.”

What is patient-controlled analgesia?

Typical pain management for scoliosis surgery called for patient-controlled analgesia — which often delivers morphine or a related opioid — during the five to seven days spent in the hospital. After that, patients were sent home with about two weeks’ worth of Oxycontin or other opioid-based painkillers. “We were already realizing that people were getting addicted very quickly,” he says. “We were asking questions: ‘Are we overdoing this?’”

What is duramorph?

At the time, an opioid medication called Duramorph was making a comeback.

While Duramorph consists of morphine, an opioid, it is given epidurally — through an injection into the area around the spinal cord — allowing doctors to control dosage and achieve pain relief at lower doses. “The beauty of Duramorph is that it’s hydrophilic,” explains Dr. Sarwahi. “It loves water, and cerebral spinal fluid is watery, so a small amount will quickly disperse along the whole spine. That provides prompt relief at a tiny dose.”

It’s 10 times more potent than the typical epidural, so it’s routinely used in microdoses during C-section deliveries.

Along with two anesthesiologists and a pain management specialist on his team, Dr. Sarwahi reviewed published studies on the use of the medication, then developed a new protocol, injecting a small dose of Duramorph directly into the spine during surgery. The idea was that preventing pain right from the start would help reduce the need for pain medication after the patient awoke. The protocol also included the use of over-the-counter medicines like acetaminophen and ibuprofen, along with muscle relaxants and, if needed, three days of opioids.

At first, the team kept patient-controlled analgesia on standby. “We expected those two teenage patients to wake up in a lot of pain, needing pain injections or even PCA, but neither of them did. We were surprised,” says Dr. Sarwahi.

The benefits of using Duramorph

After refining his use of Duramorph, Dr. Sarwahi has managed to decrease opioid use for scoliosis surgery by 80% — an astonishing reduction. And he’s working on further cutbacks. “We are now looking at the difference it makes when Duramorph is given before surgery versus at the end of surgery,” he says. He has found that even this small difference can have a big impact on the amount of opioid medication needed post-surgery.

The work with Duramorph was the first step in what Dr. Sarwahi calls his Rapid Recovery Protocol, which allows patients to go home three days after surgery versus the typical five to seven days. “Earlier, these children would wake up sluggish and drowsy. Because of the opioids, they would be nauseous and unable to eat for 24 to 48 hours, and they’d be complaining of pain despite all the pain medications they were being given,” says Dr. Sarwahi. “Now, they can start eating an hour after surgery. That means they can swallow pills, so I don’t have to give them injectable morphine.”

This national magazine highlights compelling stories about cutting-edge treatment, breakthrough medical research and lifesaving interventions.

Duramorph vs patient-controlled analgesia

Duramorph has completely replaced patient-controlled analgesia in pain management at Northwell. “We’re a zero-PCA hospital — one of very few in the world — because this protocol provides better pain control. We may still need to give opioids, but I can now send patients home with three to five days of over-the-counter acetaminophen and ibuprofen,” Dr. Sarwahi says.

Some time ago, a scoliosis patient presented Dr. Sarwahi with a gift: a video that showed her, recovered from surgery, doing gymnastic backflips. Her full return to the activities she loves reminds him of why he continues to find ways to improve treatment approaches and reduce the need for opioids. He published a paper on his pain management approach in the journal Spine in 2021 to spread the word. “I’ve successfully treated nearly 500 children using this approach,” he says. “And I haven’t looked back.”

Scoliosis surgery: a difficult procedure

In a classic operation to fix scoliosis, surgeons place rods and screws in the back after making long incisions and stripping away muscles to access the spine. So it’s no surprise that recovery can be slow and painful, or that patients on the receiving end of that treatment were often prescribed large doses of opioids.

Dr. Sarwahi pioneered a minimally invasive technique that allows him to simply separate the back muscles along their natural planes in order to access the spine instead of removing and reattaching them — a much less traumatic approach for muscles and nerves. He also makes three small incisions instead of a single long one, which produces less noticeable scarring.

That kinder, gentler technique takes a little longer in the operating room, he says, but it pays off with less pain, a faster recovery and a shorter hospital stay. There are other important benefits as well. “In a study we published a few years ago, we found that almost 99% of our patients did not need a blood transfusion, compared to 20 to 30% of patients with the older approach,” Dr. Sarwahi says. His technique has been adopted by surgeons in other countries as well as the United States.

Nerve blocks: another option for pain management

In addition to Duramorph, Northwell has also reduced opioid use with nerve blocks, anesthetic agents injected around nerves. They work by temporarily blocking the transmission of nerve signals, such as those responsible for the feeling of pain. Research has documented their use with scoliosis surgery.

Anesthesiologists have several ways of fine-tuning nerve block treatment to individual patients. Ultrasound is used to aim injections more precisely and minimize the risk of side effects like tingling in the area. Nerve blocks can also incorporate adjuvants — substances which can adjust the duration or strength of the nerve block’s effect as needed.

The benefit of nerve blocks lasts well after their effects subside. Proactively delaying and relieving pain immediately before or after surgery enables the body to start healing earlier than would otherwise be possible — reducing the need for take-home pain medication. Where a patient may need a three-week course of opioids after a surgery, patients receiving nerve blocks can get by on only two to three days of non-opioid medication like Aspirin or ibuprofen.